Steven Lester

Unstoppable

Improbable Olympian Stories as Seen Through Contemporary Paintings

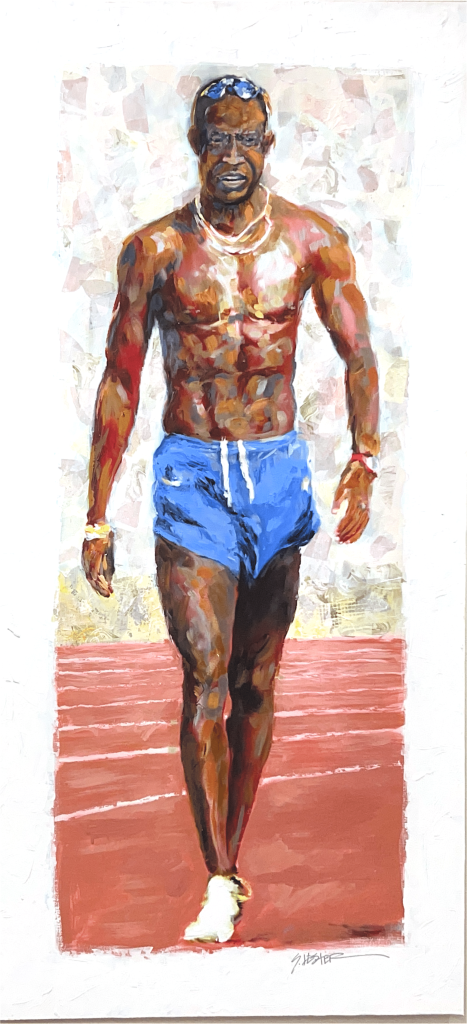

“Running for His Life”

Lopez Lomong

From South Sudanese lost boy to flag bearer for the US Olympic Team

Acrylic and collage on canvas panel, 68 x 33in

Lopez Lomong was only 6 years old when he was kidnapped from church… a Catholic caught in the crosshairs of the Second Sudanese Civil War. He was taken from his family and imprisoned, becoming one of the twenty thousand Lost Boys of Sudan.

“I was locked in prison to die,” he said. But, somehow, miraculously, a group from his village helped him escape. He spent just about 72 hours running and running, until he reached Kenya, where he lived for a decade in a refugee camp. Eventually, the Catholic Charities group paved the way for him to travel to and take up residence in the U.S.

Lomong has viewed his own life as a means through which to spread hope to others who haven’t yet reached their dreams. In 2008, he was the U.S. flag bearer during the Opening Ceremony. In 2012, he came in 10th in the 5000m finals. Dreaming bigger and climbing higher is what Lomong does best.

Today, Lopez is partnering up with World Vision to offer care, support, and a better future to families in South Sudan who are recovering from a legacy of warfare.

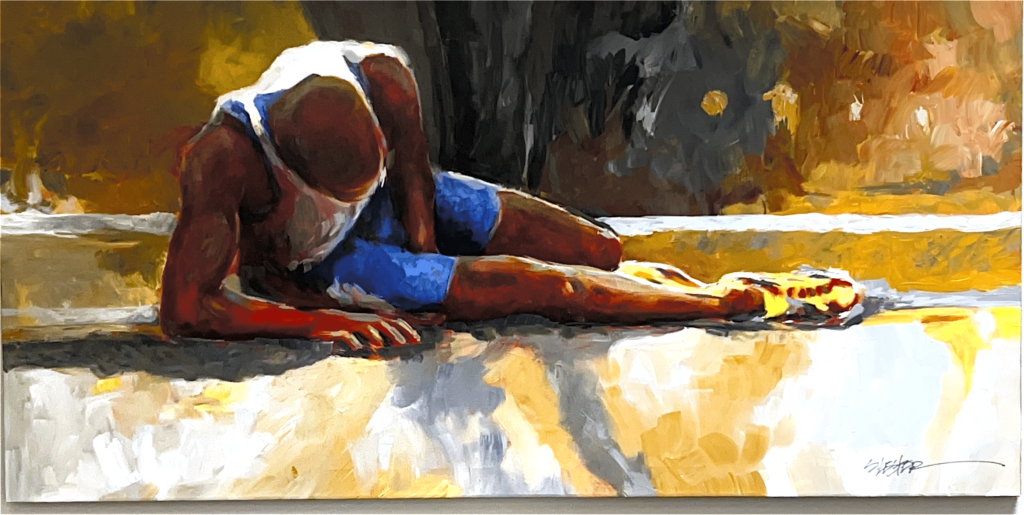

“Fallen Runner”

Derek Redmond

The fallen runner who exemplified the Olympic spirit.

Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 72 in

He may not have won a medal at the ’92 Olympic Games, but the determination that the British sprinter displayed still serves as inspiration for countless other athletes.

Redmond had been a successful track and field star and was in top form, clocking his fastest times. He started strongly in the semi-final, and was in a good position at mid-track before disaster struck. He tore his hamstring and collapsed to the ground, clutching his thigh. Medics approached with a stretcher to carry him off the track, but Redmond had other ideas. In obvious excruciating pain, he pushed himself back onto his feet and began hobbling toward the finish line.

As he struggled around the bend, Redmond’s father leapt from the crowd and made his way onto the track to help his son. In one of the most heart-warming moments ever seen, Redmond tearfully limped to the finish line, supported by his father, as the 65,000 fans in the Stadium rose to their feet to salute his bravery

“Blind Archer”

Im Dong Hyun

A blind man who can hit the bullseye every time.

Acrylic and paper collage on cradled panel, 44 x 40 in

South Korea’s Im Dong Hyun is legally blind and set the world record for men’s archery at the London Olympics. And that was no fluke the record he broke was his own from previous Olympics in Beijing and Athens. He captured gold medals there as well.

How bad is his sight? The 26-year-old has 20/200 vision in his left eye, which means he needs to be 10 times closer to see an object than someone with perfect vision. His right eye, with 20/100 vision, is not a whole lot better.

Having trouble believing this? Believe it. Im says he could not read a newspaper at arm’s length, yet he has no problem hitting a target the size of a grapefruit from a distance more than three-quarters the length of a football field.

He says he relies on distinguishing between the bright colors on the target. “When I look at the target,” he says, “it looks as if different color paints have been dropped in water… all I can do is try to distinguish between the different colors”.

In a sport that demands incredible focus and sight, Im has overcome the strongest of obstacles and hits the mark every time.

“Race Against Hate”

Jesse Owens

The Master Athlete that Humiliated the Master Race

Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 40 in

Jesse Owens was the grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper. He was born in 1913 in rural Alabama. By the age of seven he was expected to pick 100 pounds of cotton a day.

Owens was a runner and has been recognized as “the greatest and most famous athlete in track and field history”. He set three world records and tied another, all in less than an hour at the 1935 Big Ten track meet, a feat never equaled.

The 1936 Olympics in Nazi Germany were part of Adolf Hitler’s propaganda plan to prove that the “Aryan” people were the superior race. He had hoped that German athletes would dominate the games, but Jesse, a Black American, almost single-handedly upstaged Hitler’s plans. He won four gold medals, which led the people of Berlin to hail him as a hero.

Remarkably, when he returned to America after his win, he couldn’t find a job, sit in the front of the bus, or use a “whites only” water fountain. Sadly, even President Roosevelt never invited Owens to the White House, sent a telegram or acknowledged his triumphs.

A decade after his death, President George H.W. Bush awarded Owens the Congressional Medal of Honor and called his victories in Berlin “an unrivaled athletic triumph; but more than that, a triumph for all humanity.”

“Leaping Over History”

Alice Coachman

The first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal

Acrylic on canvas, 42 x 54 in

Coachman was born in 1923 in the segregated South. Young African American athletes could not use the training facilities or compete in organized sporting events. Alice had to train by running barefoot in fields and dirt roads. She would improvise by jumping over tied rags, ropes and sticks.

While still in high school, she broke both the collegiate and national high jump records. What is even more remarkable is that she did it barefooted. That is when Alice caught the attention of the Tuskegee Institute, who offered her a scholarship. At Tuskegee Alice was a champion in both basketball and track and field. In total she held an incredible 25 national titles, an even greater achievement, considering the hurdles and inequality she had to overcome.

Finally, in 1948, she was able to compete in London as a member of the American Olympic team. Despite nursing a back injury, she rose to the occasion and set a world high jump record in front of 83,000 spectators. Her Olympic gold medal was not just the first to be won by a Black woman — she was also the only American woman to win a medal of any kind at the ’48 Games.

She received her medal from the King of England and then returned home a hero. But racism didn’t take a break. On the day of Coachman’s parade and celebration in her hometown, blacks and whites were not allowed to sit together in the auditorium, and the mayor refused to shake her hand. At the conclusion of the event, she had to exit through a side door.

“Take a Deep Breath”

Michael Phelps

The most Olympic medals of all time came with its fair share of difficulties

Acrylic and resin on canvas, 24 x 48 in

Michael Phelps began swimming at the age of seven, partly because of the influence of his sisters and partly to provide him with an outlet for his energy. After retirement in 2016, he stated “The only reason I ever got in the water was my mom wanted me to just learn how to swim. My sisters and myself fell in love with the sport, and we decided to swim.” When Phelps was in the sixth grade, he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

In 2018, Phelps revealed that he has struggled both with ADHD and depression, having contemplated suicide after the 2012 Olympics. “I can tell you I’ve probably had at least half a dozen depression spells that I’ve gone through,” he said in a 2017, “And the one in 2014, I didn’t want to be alive.”

Phelps was arrested in 2014 for DUI, and he “locked himself in his bedroom for four days” after the arrest and his suspension. At 33-years-old he finally reached a point at which he is speaking about his mental health, hoping to make a difference for those who are dealing with similar issues.

Michael Phelps is the most successful and most decorated Olympian of all time, with a total of 28 medals.

“Fallen Runner”

Derek Redmond

The fallen runner who exemplified the Olympic spirit

Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 72 in

He may not have won a medal at the ’92 Olympic Games, but the determination that the British sprinter displayed still serves as inspiration for countless other athletes.

Redmond had been a successful track and field star and was in top form, clocking his fastest times. He started strongly in the semi-final, and was in a good position at mid-track before disaster struck. He tore his hamstring and collapsed to the ground, clutching his thigh. Medics approached with a stretcher to carry him off the track, but Redmond had other ideas. In obvious excruciating pain, he pushed himself back onto his feet and began hobbling toward the finish line.

As he struggled around the bend, Redmond’s father leapt from the crowd and made his way onto the track to help his son. In one of the most heart-warming moments ever seen, Redmond tearfully limped to the finish line, supported by his father, as the 65,000 fans in the Stadium rose to their feet to salute his bravery.

“Eric the Eel”

Eric Moussambani

The swimmer who had never seen an Olympic-sized pool

Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 96 in

To bring the Olympic spirit to developing nations in the late 1990s, the Olympic Committee allowed a small number of “wild card” athletes to join the Games. But because they didn’t have to go through any qualifying rounds, not all of the contenders arrived prepared. A swimmer from Equatorial Guinea named Eric Moussambani trained in a small hotel pool and had never even seen an Olympic-size pool or raced more than 50 meters. Regardless, he was determined to represent his country.

On the day of the games, Eric dove in fine, but soon began gasping for air and flailing his arms and legs. Halfway through the race, the situation looked so dire that commentators seriously worried he was drowning. When Moussambani eventually stalled out 10 meters from the end of the race, the crowd rallied and cheered him on. As he finally pulled himself from the water, the applause thundered. His final time was more than twice that of other swimmers, but his perseverance made him an Olympic celebrity, and his newfound fans dubbed him “Eric the Eel.”

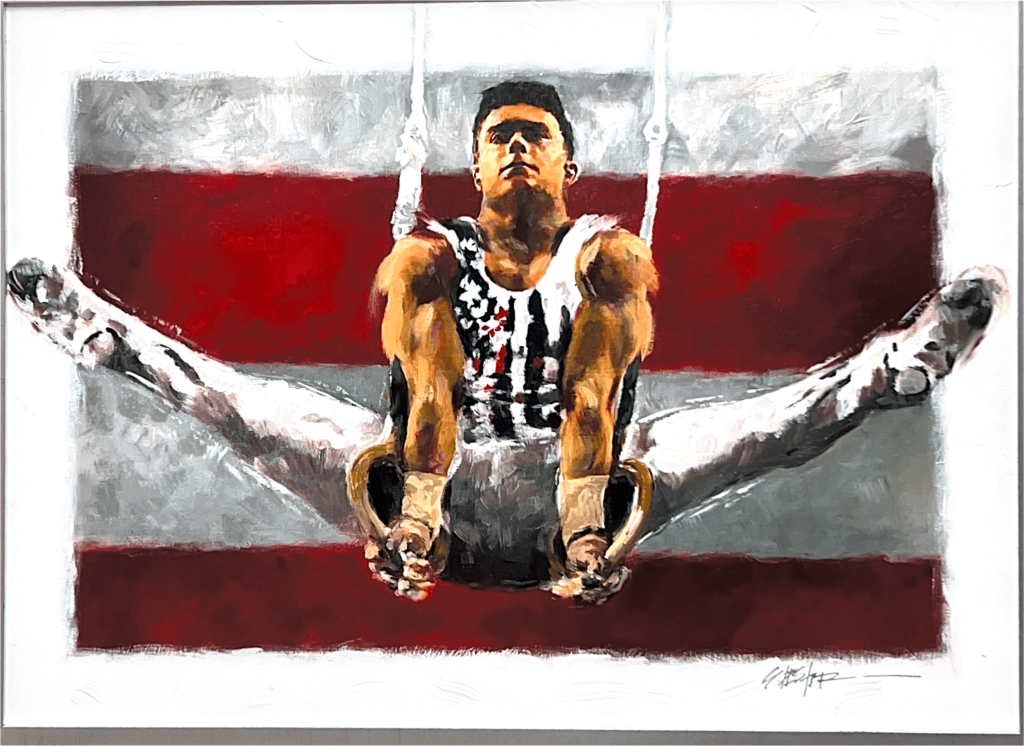

“Straining Against Adversity”

Brody Malone

The gymnast who beat came back from a career ending injury

Acrylic on canvas. 30 x 42 in

His high bar routine at a World Cup event in 2023 started off with Brody Malone cruising through the same set that had earned him a gold medal at the 2022 World Championships.

Then Malone slipped during his dismount, crashing to the mat. His right leg went one way, and the rest of his body went another. Laying on the ground in agony as the arena fell silent, his leg was fractured and multiple ligaments were shredded in his knee.

His leg might have broken, but Malone’s fighting spirit never ruptured. He braced for the first of three surgeries necessary to help him walk normally again. For anyone else, it could have been career-ending for sure. Not for the former rodeo rider who knew from experience, when you are thrown from a horse, you have to get right back up on that horse.

Growing up, Brody learned a thing or two about resilience. His mother died of cancer when he was 12 years old; seven years later, his step-mother died after a brain aneurysm. Dealing with that adversity is part of what gave him the grit and perspective to navigate his way back to an epic comeback in the competitive arena

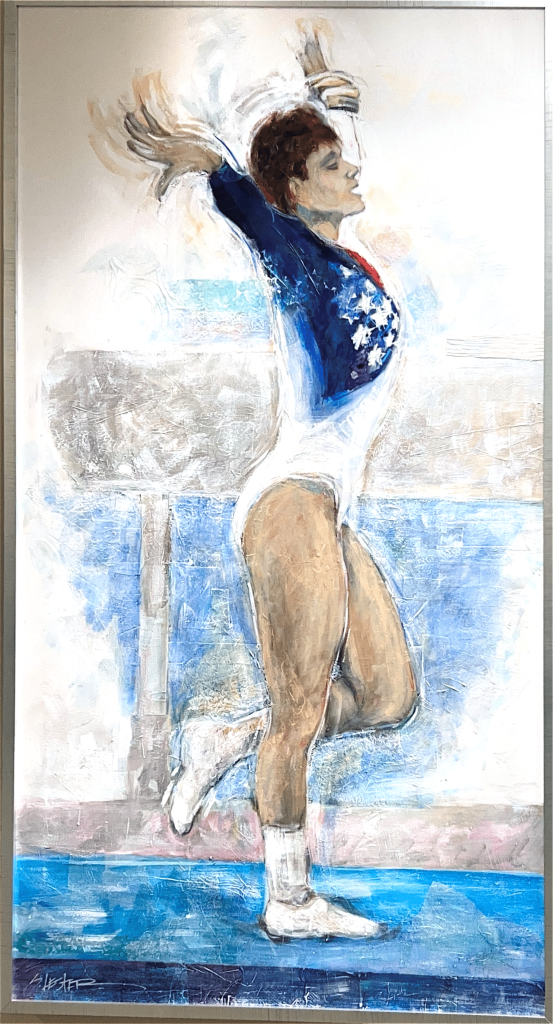

“Straining Against Adversity”

Kerri Strug

Vaulting into Olympic history on one foot.

Acrylic on Canvas, 36 x 64 in

It was the event that the Soviet Union dominated since 1952. But “The Magnificent Seven” – as they were known – were on the brink of history in the ‘96 Games in Atlanta. They were dominating the women’s all-round team event in gymnastics and a first-ever gold medal was imminent. Only the vault routine remained. Then, gut-wrenching drama.

The pressure was all on 18-year-old Kerri Strug. She had stuck vault many times in the past, but not today. Instead, as she landed, she fell back and heard a crack in her ankle and felt a sharp pain in her left ankle. Strug had one more chance to get it right but she is limping now and the pain excruciating pain became increasingly evident.

The camera then turned to Strug’s coach. He was yelling “You can do it!” repeatedly. In what would become the most talked-about moments of Olympic history, Kerri decided to let adrenaline take over put in one final heroic performance. She stuck the landing with one good ankle, lifted her left foot up and finished her routine with a smile before collapsing on the mats.

After a few seconds, it became official. The gold medal was USA’s. Strug had to be carried onto the podium and she was helped up the stairs to the podium by her teammates. It was one of the bravest displays ever seen at the Olympic Games.

In the era of Marvel and DC movies, no superhero landing can hold a candle to Strug’s unforgettable vault on an injured ankle to secure gold for the American team.

“Refuge in the Water”

Yusra Mardini

Olympic Swimmer for the Refugee Team

Acrylic on Canvas, 36 x 52 in

Yusra fled the Syrian war and set off on a perilous journey for Greece in an overcrowded dinghy. Fifteen minutes into the sea crossing, the boat’s engine failed. Yusra was determined not to let any of her fellow passengers drown. She jumped into the waves and swam for three and a half hours in open water to prevent their dinghy from capsizing, saving the lives of 20 people.

A year later, Yusra’s courage, determination and strong swimming skills were recognized by the International Olympic Committee and became a member of the first ever Refugee Olympic Team.

Yusra competed at the Olympic Games in Rio in 2016, helping to represent 65 million displaced people worldwide. Her message of hope, determination and courage reminds us that those who flee their countries are capable of achieving great things.

Mardini became the youngest-ever Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Her story is told in the biographical film titled The Swimmers, which was theatrically released and distributed on Netflix.

“Olympic Picasso”

Roald Bradstock

Improbable Olympic athlete and artist

Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 44 in

Born in England, he was diagnosed with Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus. Until age 14, he was monitored to determine if and when he would need a shunt put in. His parents were advised that he should not play contact sports. Instead he took up javelin throwing and rapidly rose to an international level.

In addition to competing in the Olympics, Bradstock also had an obsession with art. He received international attention while competing at the Olympic trials, not because he broke records, but because he wore brightly colored, hand painted outfits. He also threw hand painted javelins — each one matching a corresponding outfit. The “Olympic Picasso” was a nickname given by the media.

In 2000, he won a gold medal in painting in the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) Sport Art competition. His winning painting titled “Struggle for Perfection” went on to be exhibited at the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) Museum in Lausanne.

Bradstock later became the Executive Director of Art of the Olympians and launched a global campaign to find new Olympian and Paralympian artists. The IOC appointed him to the Olympic Culture and Heritage Commission. And at the 2018 Winter Olympic Games, Bradstock participated in the first ever Olympic Artist in Residence Project — Art created by Olympians, about Olympians.

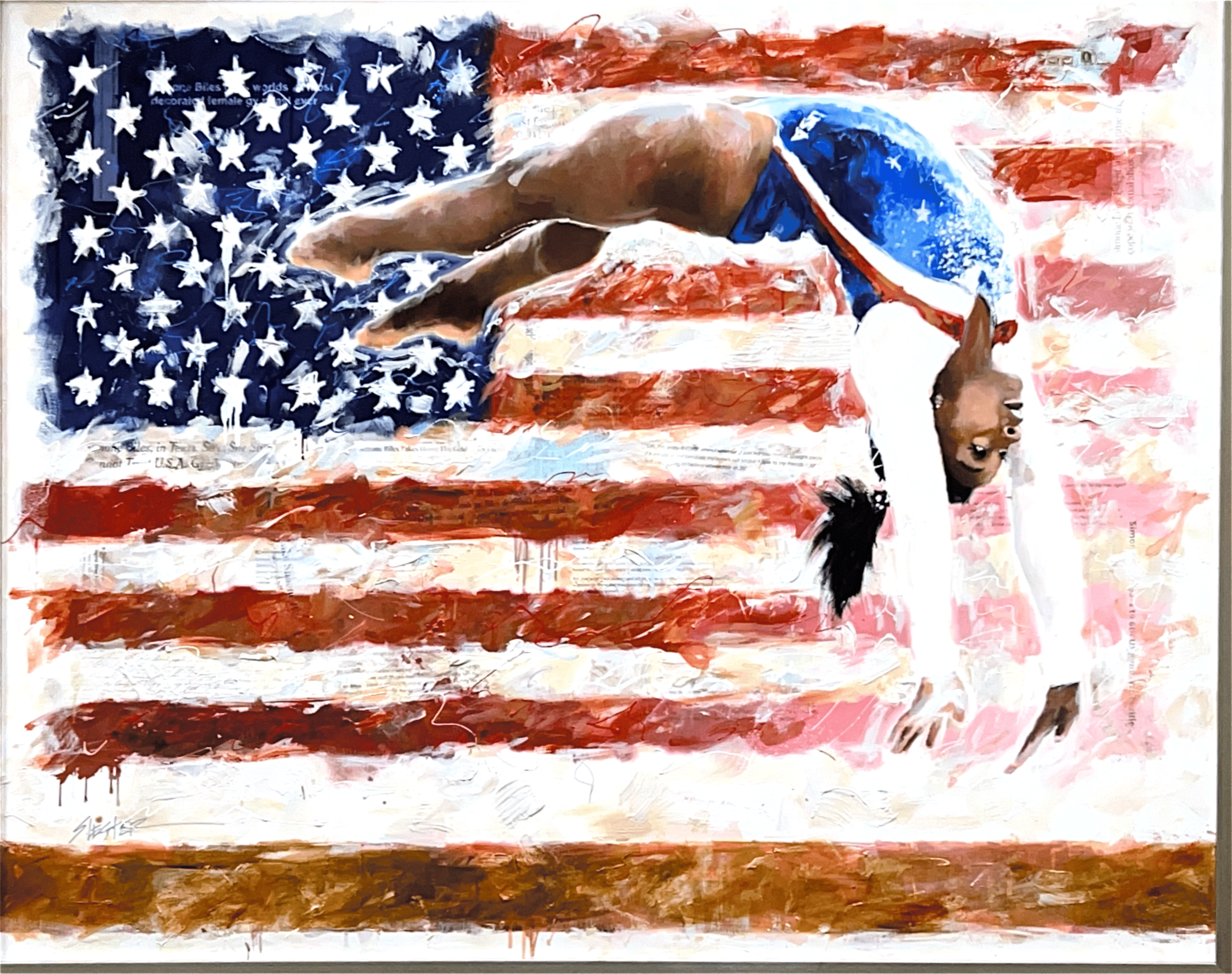

“Soaring to New Heights”

Simone Biles

Overcoming adversity and pushing the limits of athleticism

Acrylic and paper collage on cradled panel, 42 x 54 in

Gymnast Simone Biles was raised by her grandparents, after her mother’s struggle with substance abuse problem left her in foster care. She discovered her abilities at an early age after visiting a gymnastics center with her daycare group. Her talent has made her one of the top gymnasts in the world, but it was her passion and determination that has helped her persevere and overcome numerous obstacles.

Her inspiring story is filled with acts of courage. As a child, she was built very muscular and had to endure mocking and body-shaming by classmates. In grade school, she had the nickname “swoldger”—a cross between swollen and soldier. Some girls might have been crushed, but she embraced it, saying, “I’m stronger than half of the boys in my class, so don’t mess with me.” As a young African American girl in artistic gymnastics, she competed in a sport where Black athletes were rare, and she often felt out of place. In recent years, she confirmed that the former USA Gymnastics physician had sexually assaulted her, and the US Gymnastics team had covered it up. Simone has faced her share of adversity. She has had her dark days, and her moments of despair.

She remained steady and positive in the midst of a media storm and emerged from her trials stronger and more determined. She went into the arena and did her job. And she took off, tumbling, spinning, and soaring her way into the record books.